Participants

The sample size for this study was estimated using the SuperPower package (version 0.2.0; power = 0.95, standard deviation = 2) in R Studio (version 4.3.0)34. Thirty-five right-handed participants (25 females; Mage = 26 +/- 5 years; range 18–35 years) were recruited between June 2023 and November 2023 through social networks and a specific University platform for advertising experiments. Each participant received CAD 30 as compensation for participating in a three-hour session. The inclusion criterion was an age range of 18 to 35 years. Exclusion criteria included neurological disorders (e.g., traumatic brain injury), diagnosed psychological conditions (e.g., psychosis), uncorrected visual or auditory impairments, and the use of medications or substances (e.g., drugs) affecting the nervous system.

Participants completed “The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale” (HADS; Means of Anxiety score = 6.77 +/-3.3; Means of depression score = 2.94 +/-1.97) to assess mood35. This screening was run because anxiety or depression tendencies influence emotion processing36. Two participants were excluded due to high HADS anxiety scores (17 and 12, respectively)35.

Demographic information, including date of birth, gender, dominant hand, native language, and education level, was also collected (see for details). All participants provided their informed consent. Moreover, the study was approved by the UQTR ethics committee (certificate number: CERPPE-22-06-07.03) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Materials

Stimuli were sourced from the “Validation of the Emotionally Congruent and Incongruent Face-Body Static Set” (ECIFBSS)33. This dataset includes 1952 images of facial and bodily expressions (49 images/actors) presented in both congruent and incongruent situations. For this study, we selected 84 stimuli: 42 congruent (14 images per emotion: happiness, anger, and sadness) and 42 incongruent (seven images for each incongruent combination of happiness, anger, and sadness). We selected the images so that facial and bodily expressions had a relatively high and similar average recognition accuracy (94% for facial expressions and 92% for bodily expressions; OSF; ). The emotions of anger, happiness, and sadness have been selected because they are commonly employed in studies on contextual effects between facial and body cues and have been shown to elicit such effects18,37.

The ECIFBSS provided the evaluation of intensity, valence, and arousal (Table 1). Multiple ANOVAs were performed to explore differences in these emotional dimensions (valence, arousal, and intensity) as a function of emotion (happiness, sadness, and anger), congruence (congruent vs. incongruent), and mode of expression (facial vs. bodily expressions).

In terms of valence, the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of emotion (F (2,156) = 948.348, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.918), and a three-way interaction between emotion, mode of expression, and congruence (F (2,156) = 3.346, p = 0.038, η2 = 0.003). Bonferroni-adjusted paired t-tests showed that happiness was perceived as more positive than anger (t (156) =-39.411, p < 0.001, d=-7.448, CI [-3.255, -2.886]), and sadness (t (156) = 35.755, p < 0.001, d = 6.757, CI [2.601, 2.970]). Given the significant three-way interaction between emotion, congruence, and mode of expression, follow-up ANOVAs were conducted separately for each emotion to further examine the interaction between congruence and mode of expression. This analysis for sadness showed a significant main effect of mode of expression (F (1,52) = 4.106, p = 0.048, η2 = 0.069). Bonferroni-adjusted paired t-tests showed that sad faces were perceived as more negative than sad bodies (t (52) = 2.026, p = 0.048, d = 0.542, CI [0.002, 0.315]). No other significant effects were found (ps > 0.05).

In terms of arousal, the ANOVA showed a significant main effect of emotion (F (2,156) = 108.979, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.552) as well as a Congruence * Mode of expression interaction (F (1,156) = 9.668, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.024). Bonferroni-adjusted paired t-tests showed that happiness (t (156) = 14.239, p < 0.001, d = 2.691, CI [0.952, 1.332]) and anger (t (156) = 10.496, p < 0.001, d = 1.984, CI [0.652, 1.031]) were perceived as more arousing than sadness. Simple effects analysis also showed a significant effect of mode of expression during incongruent condition (F (1,156) = 9.714, p = 0.002) and a significant effect of congruence when emotions were expressed by the body (F (1,156) = 4.902, p = 0.028) and by the face (F (1,156) = 4.766, p = 0.031). No other significant effects were found (ps > 0.05).

In terms of intensity, the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of emotion (F (2,156) = 76.604, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.459), and mode of expression (F (1,156) = 8.667, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.026), as well as Congruence * Mode of expression interaction (F (1,156) = 7.716, p = 0.006, η2 = 0.023). Bonferroni-adjusted paired t-tests showed that happiness was rated as more intense than anger (t (156) =-5.464, p < 0.001, d=-1.033, CI [-1.277, -0.505]), and anger more intense than sadness (t (156) = 6.886, p < 0.001, d = 1.301, CI [0.737, 1.509]). Moreover, bodily expressions were rated as more intense than facial expressions (t (156) = 2.944, p = 0.004, d = 454, CI [0.129, 0.665]). Simple effects analysis also showed a significant effect of mode of expression in the incongruent condition (F (1,156) = 16.369, p < 0.001), and a significant effect of congruence when emotions were expressed by the body (F (1,156) = 5.182, p = 0.024). No other significant effects were found (ps > 0.05).

Given that brightness and contrast of images influence ERP components amplitudes38, we controlled these variables across stimuli (OSF; ). Brightness and contrast values were measured using ImageJ software. The mean brightness was 232.67 (+/-2.13) for congruent conditions and 232.03 (+/-2.13) for incongruent conditions. The mean of contrast was 62 (+/-3.9) for congruent conditions and 63.13 (+/-3.33) for incongruent conditions. Two one-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine potential differences in brightness and contrast between congruent and incongruent conditions. Results could not reveal significant effect of congruency on either brightness or contrast (ps > 0.154).

Finally, we used a set of 12 different and 12 identical digits to create sequences of seven random numbers. Two parameters were enforced during sequence generation: (1) no consecutive identical numbers were included (e.g., 4497425), and (2) ascending (e.g., 1234567) or descending (e.g., 7654321) sequences were avoided (OSF; ). Given that this method differs slightly from previous studies2,16,39, we conducted several pilot tests to ensure that our methodology effectively manipulated cognitive load of participants. These pilot tests helped us determine the best approach for our study.

Experimental design

The experimental design followed a within-subject approach, manipulating four independent variables: attentional focus (on face emotion or bodily expression), cognitive load (high or low cognitive load), congruency (congruent or incongruent between facial and bodily expressions), and type of emotional expression (happiness, sadness, and anger). The study consisted of a total of 672 trials, evenly divided into 336 trials per attentional focus condition (on face emotion or bodily expression). Within each attentional focus condition, there were 168 trials per congruency condition (congruency and incongruency), 168 trials per cognitive load condition (high and low), and 28 trials per emotion (happiness, sadness, or anger) in congruent situations, and 14 trials per pairs of incongruent emotions (e.g. angry face with sadness body).

General procedure

Prior to the experiment, participants completed three online questionnaires via LimeSurvey software (version 6.15.2; a socio-demographic questionnaire, the HADS35, and an informed consent and information questionnaire.

The experiment lasted approximately three hours, including one hour for the task and two hours for encephalography (EEG) equipment setup, control of impedances, and quality of signal. It was conducted in a dedicated room equipped with an EEG system at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivières (UQTR). Participants were seated comfortably on a chair inside a Faraday cage at 60 cm from a computer screen. The experiment task was programmed using E PRIME 2.0 software (version 2.0; https://pstnet.com/products/e-prime/).

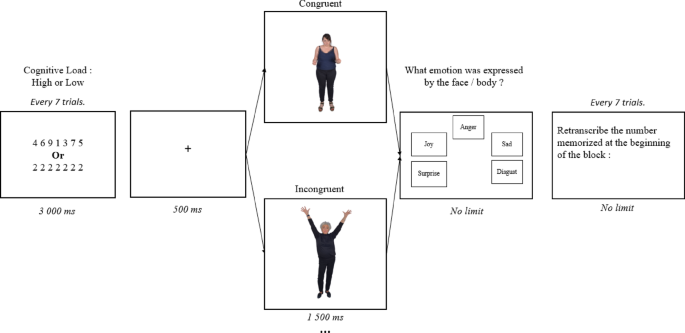

The task began with on-screen instructions, followed by two identical parts, counterbalanced in order across participants. In one part, participants focused on recognizing facial expressions, while in the other, they focused on bodily expressions. Each part started with a training session of two blocks, followed by an experimental session consisting of 48 randomized blocks. At the beginning of each block, participants were presented with a sequence of seven digits to memorize, displayed for 3000ms at the center of the screen (“Courier New” font; bold; point size 25). These sequences were either different (e.g., 4916274; representing high cognition load) or identical (e.g., 1111111; representing low cognition load). Following this, seven congruent and incongruent images were shown consecutively for 1500ms each. Each image was preceded by a 500ms fixation cross. Participants were instructed to identify the emotion expressed in either the facial or bodily expressions based on their initial impression, without time constraints. Participants had to choose, as quickly as possible, among five emotion labels: the three target emotions (anger, happiness, and sadness), plus two extra choices, disgust and surprise. Disgust was included because it is often confused with anger in incongruent face-body pairings40, which can amplify contextual effects. Surprise was also included as it is often misperceived as happiness in both facial and bodily expressions33, thereby also potentially amplifying contextual effect between these emotions. Given that surprise is an ambiguous emotion, which could be evaluated as positive or negative, it is possible that this choice might introduce variability and potentially affect the experimental outcomes. However, we believe that this influence would be minimal given that surprise was not among our target emotions but only a supplementary choice of response. After completing the emotion recognition task for all seven images in the block, participants transcribed the digit sequence they had memorized at the beginning of the block. EEG and behavioral data (accuracy and response time) were recorded simultaneously throughout the experiment (Fig. 1).

Shema of block structure.

The block was constituted of the presentation of digits, a fixation cross, a picture of emotionally congruent or incongruent face and body expressions, a prompt for emotional identification. Every seven trials, participant had to write the digits they had memorized.

Statistics analysis

The behavioral and EEG data were analyzed using MATLAB (R2021a; JASP (version 0.18.1; RRID: SCR_015823; and R (version 4.3.0; The package ggplot2 (version 3.4.2; RRID: SCR_014601; https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/)41, tidyverse (version 1.2.0; RRID: SCR_019186; https://www.tidyverse.org/)42, dplyr (version 1.1.2; RRID: SCR_017102; https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/)43, and emmeans (version 1.8.7; RRID: SCR_018734; https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans)44 were used. The analyses conducted are available on the OSF platform ().

Behavioral analysis

First, we analyzed data from the memorization task. A paired t-test and a Bayesian t-test were performed on digit memorization scores to examine differences between cognitive load levels. Additionally, a Pearson correlation was conducted between digit memorization and emotion recognition accuracy to assess their association. Further analyses were conducted on trials where participants achieved a 100%-digit memorization rate. Trials with incorrect digit memorization were excluded from further analysis.

Secondly, we analyzed the emotion recognition task. Behavioral data were assessed using two metrics: the accuracy rate of correct categorization and response time. For accuracy, we calculated the Unbiased hit rates (Hu score)45 for emotion recognition. This metric adjusts for potential response bias that could inflate accuracy score. For instance, a participant who categorizes all facial expressions as “anger” may achieve a high accuracy score for anger, but this does not indicate true recognition. The Hu score corrects this bias by considering the squared frequency of correct responses for a target emotion, divided by the product of the total number of stimuli representing that emotion and the overall frequency of selecting that emotion category45. To identify and exclude outliers in both Hu scores and response times, we used the Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) function in R46,47.

We conducted classical repeated measures ANOVAs on the arcsine-transformed Hu score as recommended in the literature45,48 and response times, incorporating three factors: congruency, attentional focus, and cognitive load. Since classical repeated measures ANOVAs do not allow for direct support of the null hypothesis (i.e., no difference between conditions), we complemented these with repeated measures Bayesian ANOVAs using the same factors. For Bayesian analyses, we used default prior options for effects (r = 0.5 for the fixed effects) as recommended29,31. The Bayesian ANOVAs produced two types of models: the null model and the alternative model. Alternative models included one or more factors and interactions between them. JASP software calculated Bayes factors (BF10) for each model, quantifying the strength of evidence in favor of each alternative model relative to the null model or the best-performing model30. In other words, a BF10 ratio indicates how much more likely the observed data are under an alternative model (i.e., the most likely model) compared to the null model. Evidence for the null hypothesis is indicated by BF10 values between 1 and 1/3 (weak evidence), between 1/3 and 1/10 (moderate evidence), and below 1/10 (strong evidence). Conversely, B10 values between 1 and 3 (weak evidence), 3 and 10 (moderate evidence), and above 10 (strong evidence) support the alternative hypothesis28,31. For example, a BF10 of 30 indicates that the data are thirty times more likely to occur under the alternative model than the null model29. Additionally, we calculated inclusion Bayes factor (BFinclusion) for each factor (congruency, focus, and cognitive load) to quantify the evidence for including these factors and their interactions within the set of models. This approach allowed us to assess the predictive value of each factor in the dataset29.

ERP recording, preprocessing, and analysis

BrainVision Recorder software (version 1.27.0001; was used to record EEG data. EEG activity was recorded from 64 scalp electrodes, with Fpz serving as the ground electrode. Data were sampled at a rate of 500 Hz per channel for offline analysis. Additionally, the vertical electrooculogram (VEOG) and horizontal electrooculogram (HEOG) were recorded using three electrodes: below the left eye (Fp2), and on the left (FT9) and right (FT10) sides of the eyes. Two electrodes (TP9 and TP10) were placed on the earlobes as reference electrodes. All electrode impedances were kept below 25 kΩ.

Data pre-processing was performed using the EEGLab (version 2024.2.1; https://eeglab.org/others/How_to_download_EEGLAB.html)49 and ERPLAB (version 12.01; https://github.com/ucdavis/erplab/releases/tag/12.01)50 toolboxes in MATLAB, following the pipeline outlined by Lopez-Calderon and Luck50. The data were re-referenced offline to the average and filtered with a 0.1 Hz high-pass filter. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was performed by the first author (ASP) using AMICA51. The signals were segmented into epochs ([-200ms; 700ms]) around the target stimuli. A low-pass filter with a cutoff at 30 Hz was applied, followed by two rounds of artifact detection. The first round used the “moving window peak-to-peak threshold” method from ERPLAB, with a threshold of 100uV, a window size of 200ms, and a window step of 100ms. The second round targeted eye movements at electrodes 5, 25, and 30, using the “step-like artifacts” detection method, with a threshold of 30uV, a window size of 200ms, and a window step of 50ms. After artifact rejection, an average of 96.5% of data was retained for further analysis (Face focus: 97.57%; body focus: 95.46%; Congruency: 96.72%; Incongruency: 96.42%; High cognitive load: 96.53%; Low cognitive load: 96.52%). As in the behavioral analyses, EEG analyses were only conducted on trials in which participants achieved a 100%-digit memorization rate. Trials with incorrect digit memorization were excluded. On average, 77.71% of the data (M = 539.5 trials) was retained for analysis (Face focus: 77.91% (M = 268.25 trials); body focus: 77.1% (M = 271.25 trials); Congruency: 78.35% (M = 271.46 trials); Incongruency: 77.14% (M = 268.04 trials); High cognitive load: 65.64% (M = 227.25 trials); Low cognitive load: 89.91% (M = 312.25 trials)).

The Factorial Mass Univariate Toolbox (FMUT; version 0.5.1; RRID: SCR_018734; was used to analyze the EEG data52. This analysis involves iteratively conducting thousands of inferential statistical tests and applying multiple comparison corrections across all electrodes within a temporal window of interest52,53,54,55,56. Mass univariate analyses provide an exploratory approach to identifying effects without requiring a priori assumptions and offer greater power for detecting effects compared to traditional spatiotemporal averaging methods52,57.

We first conducted an exploratory mass univariate analysis on all electrodes and time points from − 100ms pre-stimulus to the end of the epoch (700ms). Based on this exploratory analysis and previous work3,17,58,59, we identified two early time windows of interest at fronto-central sites (F1, F2, F3, F5, F6, FC1, FC2, FC3, FC5, Fz, and FCz) during the P100 (70-140ms) and N250 (150–318ms) and at parieto-occipital sites (PO7, PO8, PO4, PO3, P5, P6, P7, P8, O1, O2, and Oz) during the P100 (70-140ms) and P250 (150–318ms). We also identified one later time window in the centro-parietal (Cz, C1, C2, C3, C4, CPz, CP1, CP2, CP3, CP4, Pz, P1, P2, P3, and P4) and occipital sites (O1, O2, and OZ; 200–700ms).

Mass univariate analysis used an alpha level of 0.05 and was performed with three within-subjects factors: cognitive load, focus, and congruence. In FMUT, ANOVAs were conducted using 100,000 permutations for each data point, with correction for multiple comparisons via permutation test, as recommended52,53,54. Finally, we also conducted repeated-measures Bayesian ANOVAs on the amplitude of components averaged over the same time windows and electrode sites as the FMUT analysis, using the three factors: cognitive load, focus, and congruence.

link